The Poetics of Gnosticism, Materialism, and the Incarnation

Wallace Stevens' Modern Gnosticism

There is no knowledge of reality directly. Instead, the mind creates reality through perception. [Description = Perception = Conception] Poetry bestows meaning on the (meaningless) universe. It does this because the mind locates a pattern in what otherwise seems random. Poetry can achieve a "supreme fiction" that allows us to order and create purpose. In this sense, the imagination enhances experience. Poetry must be abstract, changeable, and yet give pleasure, for it is a thing of the mind. It also has a particular music, a euphony, that sets it apart from daily language. For poetry to be affective it must have original ideas: "In the absence of a belief in God, the mind turns to its own creations and examines them, not alone from the aesthetic point of view, but for what they reveal, for what they validate and invalidate." In contrast, "the trash heap of history" is the place for worn-out ideas that no longer move us. Symbolism is particularly important, for it gives poetry a way to "inspire" the particulars of the world. Symbols are also what give significance (or at least interest) to the human struggle.

where I was born? knowing

how futile would be the search

for you in the multiplicity

of your debacle. The world spreads

for me like a flower opening -- and

will close for me as might a rose --

wither and fall to the ground

and rot and be drawn up

into a flower again. But you

never wither -- but blossom

all about me. In that I forget

myself perpetually -- in your

composition and decomposition

I find my . . . despair!

-- from Book 2, Patterson [In the manuscript, Williams had addressed this to "God"]

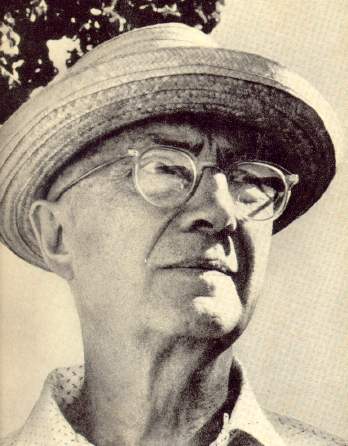

William Carlos Williams' Impulse Towards Enlivened Materialism

The most famous phrase associated with Williams is "No ideas but in things." He stressed that poetry should seek to impart a vivid realism of the active things of life. Williams was deeply opposed to symbolism, distrusted overuse of figurative language, and (at least for a portion of his life) avoided metaphysics. He did hold that life, particularly nature, had some kind of power innate to it, though he never quite understood this as divine. He tended to distrust universals. In reaction to positions like Stevens, he wrote, "I do not believe that writing is music." He felt that poems were shaped objects designed to "lift up the word of the senses to the level of the imagination and so give it a new currency." But this does not mean that he believed that the words used by a poet actually spoke for reality. Instead, he stressed that words and things are two separate elements. In some sense, the poem is a natural thing itself.

it must be "lit with piercing glances into the life of things";

it must acknowledge the spiritual forces which have made it."

-- "When I Buy Pictures"

. . . To explain grace requires

a curious hand. If that which is at all were not forever,

why would those who graced the spires

with animals and gathered there to rest, on cold luxurious

low stone seats -- a monk and monk and monk -- between the thus

ingenious roof-supports, have slaved to confuse

grace with a kindly manner, time in which to pay a debt,

the cure for sins, a graceful use

of what are yet

approved stone mullions branching out across

the perpendiculars?

-- "The Pangolin"

Marianne Moore's Incarnational Humility

Moore, a Presbyterian Christian, holds that all good poetry is a result of a mixture of objective and subjective elements. The objects that a poet writes about are a product of her perception, but also real objects that act on the poet. She stresses that in a fallen world, poetry is imperfect in its ability to discover and capture the moment, and yet that inability is its strength: "Humility is an indispensable teacher, ennabling concentration to heighten gusto. [. . .] The thing is to see the vision and not deny it; to care and admit that we do." Poets do not create truths; poets' genius comes from their sincerity and craft, not some "capture" of truth in form. She stresses that true poets are "literalists of the imagination," ones who see the genuine, raw subjects of the world engraced with transcendent power. She also insists that her extensive use of quotations are a form of genuine community: "If you are charmed by an author, I think it's a very strange and invalid imagination that doesn't love to share it." Poetry is both personal and objective. Such careful observation is a product of the contemplative mind.

Coda: A poetics like Moore's reminds us that all poetry can be read incarnationally -- the poem of ideas can be read as poets' failable attempts to speak of their personal conceptions; the poem of objects can be understood as bright attempts at naming the value in creation. They can teach us in their valuable limitedness.