The Club of Queer Trades and the Fourth-Rate Civilization

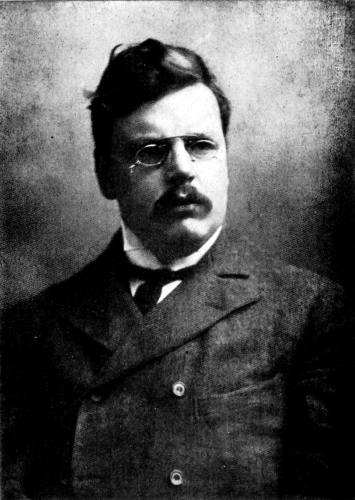

G.K. Chesterton's early "detective" collection, The Club of Queer Trades (1904), merges the genre of Sherlock Holmes with that of Alice in Wonderland, offering us a central character who in his supposed madness is in truth the only one who sees things for what they are. Indeed, every revelation of the case is one in which nothing substantial has gone wrong, yet the implication remains that something is lacking in the modern world of the characters. By doing this, Chesterton makes Basil Grant an implicit, and often explicit, critique of late Victorian, early Edwardian culture, especially in regards to its claims of progress, reason, empiricism, and evolutionary superiority. Chesterton carries out this critique in a manner light and humorous, as playful as it is insightful. This manner is, in part, the result of his illustrations, which are each character studies that interact with the story itself. By playing off various general "types" Chesterton asks us to:

- Get the joke--the types have behaviors that are in turn observed with realistic detail, exaggerated for effect, or placed in ironic situations;

- Notice something about human psychology--part of the humor is in quickly deciding as a reader whether the funny behavior is too true to life, an eccentric exception, or an extreme version of its normal, laughable counterpart;

- Get the context--the "fourth-rate civilization" (85) of fin-de-siecle London is one of material plenty for some, but boredom and ennui for many.

- Ask the big questions--though the manner of Chesterton's collection is breezy and eccentric, the large, metaphysical questions of truth, beauty, ethics, human origins, and faith come up again and again.

Discussion Questions

"The Tremendous Adventures of Major Brown"- What are the nature of Basil Grant's moral and spiritual concerns? What makes his brother Rupert different?

- Is Basil right to claim that "the facts often obscure the truth"? (67)

- Why is there a modern need for romance and adventure? (77-79) Is that still true today?

- Why does the actress marry the major in the end? How does this event evaluate the remainder of the story?

- Why does Basil distinguish between trying to be good and trying to be evil?

- Why does he distinguish facts from spiritual impressions? (88) Why does he trust the later?

- What character type is Lord Beaumont of Foxwood? What is Chesterton making fun of by this type?

- How are we as readers to feel about Drummond? Explain your answer.

- Why is the organizer of repartee immoral? Do you agree?

- How does the story embody the narrator's opening observation that "[i]t is the small things rather than the large things which make war against us and, I may add, beat us"?

- Should this story we defined as a romance? Why or why not?

- Is Basil important or insightful in this story? Explain.

- Is Shorter right to defend himself as performing only "a social fiction. A result of our complex society"?

- Try to summarize for yourself the quality of Drummond Keith. Is it possible?

- How does this story again explore the nature of truth and fiction, facts versus reality? Why do Rupert and Swinburne lack insight?

- What is Chadd's theory of language?

- How does Basil undercut that theory?

- What is at stake in the evolutionary theory of language and culture? (cf. 159-160)

- Why does Basil decide to speak/dance with Professor Chadd at the end?

- How does the theory of evolution and Darwinian ethics arise in this story? Why is it important?

- What makes Basil's own queer trade important to the story? And for that matter, all the stories?

- Does the club have a serious purpose? Explain.