Early Modern Family Life (1600-1789)

"Now where the husband and wife performeth these duties in their house, we may call it a college of quietness. The house wherein these are neglected, we may term it a hell."

--John Dod and Robert Cleaver, A Godly Form of Household Government

"The third thing whereunto a servant is called is to serve, that is, to obey and to be in subjection, to have no will of his own or power over himself, but wholly to resign himself to the will of his Master, and this is to obey."

--Thomas Fosset, The Servant's Duty

In examining family life in history, it is important to keep in mind that the ideals and the actual practice do not often match up, as perhaps we all know, no matter how satisfactory or unsatisfactory our own family life may be or have been growing up. Therefore, when looking at domestic history, one has to hold in tension the various texts--sermons, advice manuals, paintings, and so on--that model what people wanted family life to be like with indicators of what it often actually was like--letters, social statistics, legal and municipal records, satires and comedies, etc. Places where the ideal and the actual sometimes did not meet included:

- Family Authority--in particular, the assumed authority of the husband and father over wife and children and the resulting expected obedience and deferment.

- Gender Roles--the kinds of work, behavior, and dress appropriate for men and women was debated, as was the the appropriateness of popular entertainments.

- Legal Rights & Responsibilities--for example, the right to own property was typically denied to wives, but opened up to widows.

- Domestic Wealth--differences between how the various classes lived include houses, furniture, luxuries, clothing, diet, and so forth. What was considered appropriate for one's station and social standing was often debated, too.

- Education--especially in the 18th century, a large debate was held in various public venues as to whether women should be formally educated and if so, what that education should entail.

- Marriages, Divorces, Estrangements--marriage was a often a matter of families exchanging wealth for status, or expanding wealth and status, or maintaining those matters. Divorces were almost impossible to obtain.

- Sexual Behavior--contradictory expectations and double-standards for husbands and wives are only one of the potential points of tension; another is the nature of conjugal relations within marriage, including concerns with intimacy and pleasure. Illegitimacy was also of particular concern when considering inheritance laws and practices.

Likewise, one should keep in mind that it is impossible to draw generalizations across all of Europe (or America) in this period. Differences in region, class, religion, country, and age account for important differences in family life. John Hajnal has suggested that broadly Western Europe tended to observe a marriage pattern involving later marriage (men 26-27, women 23-24) with 10-15% never marrying, while in Eastern Europe, men and women married younger and almost all were married. In the same way, urban areas had more nuclear families with higher fertility rates and more persons living alone.

Household structures were diverse and in different proportions in differing regions:

- nuclear families: husband-wife-children

- "non-family" households: household with individuals or siblings

- multiple families: two or more families with some linage relationship

- extended families: nuclear family plus other family members such as aging parent, unmarried brother, etc.

- stem families: single son with parents

- neolocal families: nuclear families in separate, but nearby households

Systems of inheritance included partible ones where all sons divided the inheritance, inpartible ones in which the eldest son received all or the largest portion (fiedicommisum or progenitur and entail), and later on partible ones that included daughters.

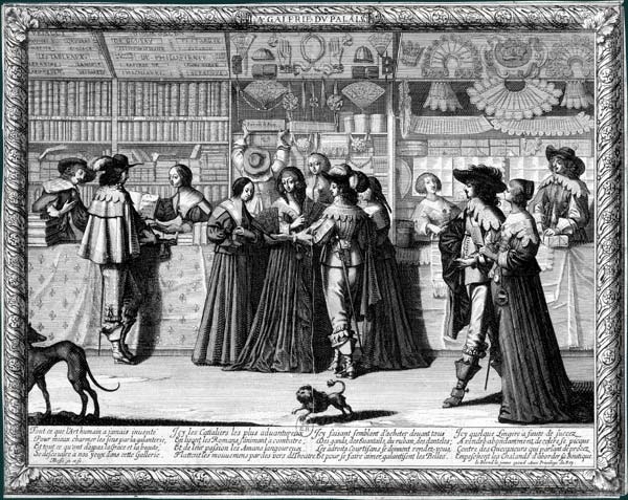

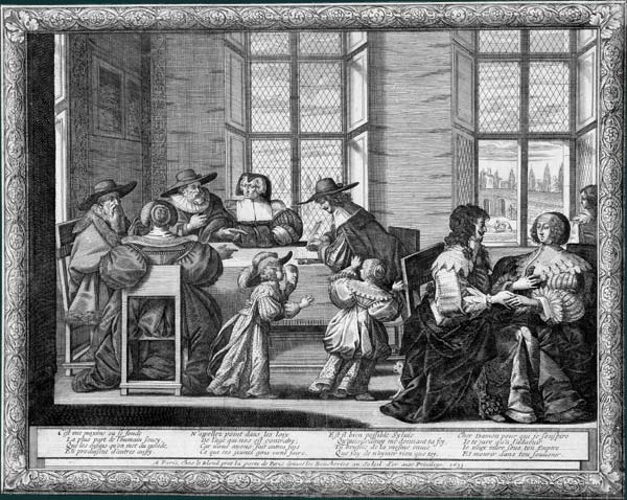

Abraham Bosse (French engraver, c.1602-1676)

The following images by Bosse represent various aspects of French upper middle class life in the 17th century. What does each suggest about the nature of domesticity, family relations, entertainment, manners, and consumerism?