Definitions and Characteristics of Modernity

Since the term "Modern" is used to describe a wide range of periods, any definition of modernity must account for the context in question. Modern can mean all of post-medieval European history, in the context of dividing history into three large epochs: Antiquity, Medieval, and Modern. Likewise, it is often used to describe the Euro-American culture that arises out of the Enlightenment and continues in some way into the present. The term "Modern" is also applied to the period beginning somewhere between 1870 and 1910, through the present, and even more specifically to the 1910-1960 period.

One common use of the term, "Early Modern" is to describe the condition of Western History either since the mid-1400's, or roughly the European discovery of moveable type and the printing press, or the early 1600's, the period associated with the rise of the Enlightenment project. These periods can be characterized by:

- Rise of the nation state

- Growth of tolerance as a political and social belief

- Industrialization

- Rise of mercantilism and capitalism

- Discovery and colonization of the Non-Western world

- Rise of representative democracy

- Increasing role of science and technology

- Urbanization

- Mass literacy

- Proliferation of mass media

- The Cartesian and Kantian distrust of tradition for autonomous reason

In addition, the 19th century can be said to add the following facets to modernity:

- Emergence of social science and anthropology

- Romanticism and Early Existentialism

- Naturalist approaches to art and description

- Evolutionary thinking in geology, biology, politics, and social sciences

- Beginnings of modern psychology

- Growing disenfranchisement of religion

- Emancipation

Defining Characteristics of Modernity

There have been numerous attempts, particularly in the field of sociology, to understand what modernity is. A wide variety of terms are used to describe the society, social life, driving force, symptomatic mentality, or some other defining aspects of modernity. They include:

- Bureaucracy--impersonal, social hierarchies that practice a division of labor and are marked by a regularity of method and procedure

- Disenchantment of the world--the loss of sacred and metaphysical understandings of al facets of life and culture

- Rationalization--the world can be understood and managed through a reasonable and logical system of objectively accessible theories and data

- Secularization--the loss of religious influence and/or religious belief at a societal level

- Alienation--isolation of the individual from systems of meaning--family, meaningful work, religion, clan, etc.

- Commodification--the reduction of all aspects of life to objects of monetary consumption and exchange

- Decontexutalization--the removal of social practices, beliefs, and cultural objects from their local cultures of origin

- Individualism --growing stress on individuals as opposed to meditating structures such as family, clan, academy, village, church

- Nationalism--the rise of the modern nation-states as rational centralized governments that often cross local, ethnic groupings

- Urbanization--the move of people, cultural centers, and political influence to large cities

- Subjectivism--the turn inward for definitions and evaluations of truth and meaning

- Linear-progression--preference for forms of reasoning that stress presuppositions and resulting chains of propositions

- Objectivism--the belief that truth-claims can be established by autonomous information accessible by all

- Universalism--application of ideas/claims to all cultures/circumstances regardless of local distinctions

- Reductionism--the belief that something can be understood by studying the parts that make it up

- Mass society--the growth of societies united by mass media and widespread dissemination of cultural practices as opposed to local and regional culture particulars

- Industrial society--societies formed around the industrial production and distribution of products

- Homogenization--the social forces that tend toward a uniformity of cultural ideas and products

- Democratization--political systems characterized by free elections, independent judiciaries, rule of law, and respect of human rights

- Mechanization--the transfer of the means of production from human labor to mechanized, advanced technology

- Totalitarianism--absolutist central governments that suppress free expression and political dissent, and that practice propaganda and indoctrination of its citizens

- Therapeutic motivations--the understanding that the human self is a product of evolutionary desires and that the self should be assisted in achieving those desires as opposed to projects of ethical improvement or pursuits of public virtue

Modernity is often characterized by comparing modern societies to premodern or postmodern ones, and the understanding of those non-modern social statuses is, again, far from a settled issue. To an extent, it is reasonable to doubt the very possibility of a descriptive concept that can adequately capture diverse realities of societies of various historical contexts, especially non-European ones, let alone a three-stage model of social evolution from premodernity to postmodernity. As one can see above, often seemingly opposite forces (such as objectivism and subjectivism, individualism and the nationalism, democratization and totalitarianism) are attributed to modernity, and there are perhaps reasons to argue why each is a result of the modern world. In terms of social structure, for example, many of the defining events and characteristics listed above stem from a transition from relatively isolated local communities to a more integrated large-scale society. Understood this way, modernization might be a general, abstract process which can be found in many different parts of histories, rather than a unique event in Europe.

In general, large-scale integration involves:

- Increased movement of goods, capital, people, and information among formerly separate areas, and increased influence that reaches beyond a local area.

- Increased formalization of those mobile elements, development of 'circuits' on which those elements and influences travel, and standardization of many aspects of the society in general that is conducive to the mobility.

- Increased specialization of different segments of society, such as the division of labor, and interdependency among areas.

Seemingly contradictory characteristics ascribed to modernity are often different aspects of this process. For example, unique local culture is invaded and lost by the increased mobility of cultural elements, such as recipes, folktales, and hit songs, resulting in a cultural homogenization across localities, but the repertoire of available recipes and songs increases within a area because of the increased interlocal movement, resulting in a diversification within each locality. (This is manifest especially in large metropolises where there are many mobile elements). Centralized bureaucracy and hierarchical organization of governments and firms grows in scale and power in an unprecedented manner, leading some to lament the stifling, cold, rationalist or totalitarian nature of modern society. Yet individuals, often as replaceable components, may be able to move in those social subsystems, creating a sense of liberty, dynamic competition and individualism for others. This is especially the case when a modern society is compared with premodern societies, in which the family and social class one is born into shapes one's life-course to a greater extent.

At the same time, however, such an understanding of modernity is certainly not satisfactory to many, because it fails to explain the global influence of West European and American societies since the Renaissance. What has made Western Europe so special?

There have been two major answers to this question. First, an internal factor is that only in Europe, through the Renaissance humanists and early modern philosophers and scientists, rational thinking came to replace many intellectual activities that had been under heavy influence of convention, superstition, and religion. This line of answer is most frequently associated with Max Weber, a sociologist who is known to have pursued the answer to the above question. Second, an external factor is that colonization, starting as early as the Age of Discovery, created exploitative relations between European countries and their colonies.

It is also notable that such commonly-observed features of many modern societies as the nuclear family, slavery, gender roles, and nation states do not necessarily fit well with the idea of rational social organization in which components such as people are treated equally. While many of these features have been dissolving, histories seem to suggest those features may not be mere exceptions to the essential characteristics of modernization, but necessary parts of it.

Modernity as Hope, Modernity as Doom

Modernization brought a series of seemingly indisputable benefits to people. Lower infant mortality rate, decreased death from starvation, eradication of some of the fatal diseases, more equal treatment of people with different backgrounds and incomes, and so on. To some, this is an indication of the potential of modernity, perhaps yet to be fully realized. In general, rational, scientific approach to problems and the pursuit of economic wealth seems still to many a reasonable way of understanding good social development.

At the same time, there are a number of dark sides of modernity pointed out by sociologists and others. Technological development occurred not only in the medical and agricultural fields, but also in the military. The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, and the following nuclear arms race in the post-war era, are considered by some as symbols of the danger of technologies that humans may or may not be able to handle wisely. Stalin's Great Purges and the Holocaust (or Shoah) are considered by some as indications that rational thinking and rational organization of a society might involve exclusion, or extermination, of non-standard elements.

Environmental problems comprise another category in the dark side of modernity. Pollution is perhaps the least controversial of these, but one may include decreasing biodiversity and climate change as results of development. The development of biotechnology and genetic engineering are creating what some consider sources of unknown risks.

Besides these obvious incidents, many critics point out psychological and moral hazards of modern life - alienation, feeling of rootlessness, loss of strong bonds and common values, hedonism, disenchantment of the world, and so on. Likewise, the loss of a generally agreed upon definitions of human dignity, human nature, and the resulting loss of value in human life have all been cited as the impact of a social process/civilization that reaps the fruits of growing privatization, subjectivism, reductionism, as well as a loss of traditional values and worldviews. Some have suggested that the end result of modernity is the loss of a stable conception of humanity and/or the human being.

[Much of the above is taken from Wikipedia’s free article. In conjunction with the website's philosophy, I have freely adapted materials, added my own, and deleted other selections without clear attribution. Anyone who wants to see the full article may go to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modernity]

Conditions of the Modern Self

- The modern self assumes an autonomy that seeks to reject the claims of authority, tradition, or community.

- The modern self searches for personal therapy that only results in the subjective experience of well-being.

- The true, the good, and the beautiful are undiscoverable, so they are judged as not applicable to human experience.

- The modern self has moved from an emphasis on redemption of character to liberation from social inhibitions.

- Identity is self-constructed through self-consumption of products of desire.

- Such claims about identity and truth call for a technical mastery of the environment, as well as a division between the public and private spheres of reality.

Adapted from Gay, Craig M. The Way of the (Modern) World: Or, Why It's Tempting to Live As If God Doesn't Exist. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

Peter Berger's Six Propositions on The Nature of Western Individuality

Thus, with the above in mind, this is how most of Western society understands human identity:

- The uniqueness of the individual represents his or her essential reality.

- Individuals are or ought to be free.

- Individuals are responsible for their own actions, but only for their own actions.

- An individual's subjective experience of the world is "real" by definition.

- Individuals possess certain rights over and against collectives.

- Individuals are ultimately responsible for creating themselves

Berger, Peter L. "Western Individuality: Liberation and Loneliness," Partisan Review52 (1985).

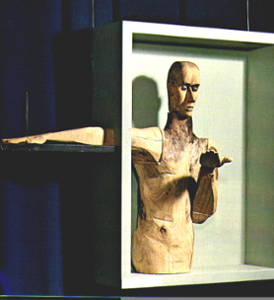

The image above is of Torsten Renqvist's 1971 Ordet. It is an image of Christ. I have chosen to include it here because it represents a very Romantic notion of Christ, one who is a self-actualized hero. Christ projects himself by force of will outside of his circumstances. By the power of his imagination he overcomes the wounding he receives in his hands. Renqvist's vision of Christ is essentially a modernist one, in which creed and religion have been reduced to a therapeutic desire for internal expression. In this sense, Ordet is emblematic of the false solutions that the modern self is left with.