Aspects of Various Periods in the Western, Euro-American Tradition

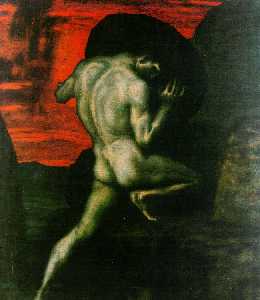

Baroque (ca. 1580-1680)

- A blending of the picturesque (the wild, the unexpected, the fantastic) with Renaissance formalism.

- Stress on movement, energy, and realism

- Discord and suspension is set within a heightened, rhetorical emphasis

- Its use of asymmetry, rough form, and obscurity could sometimes lead to an emphasis on the grotesque and the contorted

- The practice of the metaphysical conceit, a strong, unexpected analogy between two objects intended to enlighten both the reason and the emotions

- Tends to focus on the analytical, psychological, and commonplace.

- Often absorbed with thoughts of love, death, and religious devotion.

Aspects of Neo-Classicism and the Enlightenment (ca. 1630-1780)

- Stress on reason and the scientific method.

- A belief in the perfection of human nature and society; universally valid principles of nature and society are discoverable

- Even faith is rational; God is reasonable and obeys accepted rational standards. (As a result, this leads many to discount or disbelieve entirely any emphasis on the supernatural)

- Reliance on models of classical Greece and Rome (e.g. the three unities)

- Reverence for order and accepted rules.

- Stress on good taste, decorum, unity, harmony, proportion, and grace in art. Art’s purpose is "to teach" and "to delight."

- Stress on public life, the role of tradition, and sociability stress codes of manners and networks of dependency.

- Traditional hierarchical relationships are (slowly) giving way to republican and mercantile models of government and economics.

- Distrust of invention and extreme displays of emotion, an interest in sentiment and sublimity. The comic is intended to mock lapses in these ideals.

Aspects of Romanticism (ca. 1780-1870)

- Shifts in intellectual and cultural emphasis:

- from reason to emotion and imagination;

- from developed to primitive;

- from universal to particular;

- from humanity to nations;

- from community to individuals;

- Feelings as the judge of truth. Intuition and instinct become acceptable if not dominant models for uncovering the reality.

- The theory and practice of revolution: the purging of the old, corrupt society to make way for the new and innocent; stress on liberty and freedom from restraint; individuals will do what is right if freed from authority

- The rise of the commercial class and the Industrial Revolution

- History as a primal force of Necessity or World Soul

- The self as the final arbitrator of what is real and right. The sacredness of the individual.

- The artist or poet moves from having genius to being a genius, from being a maker, one who imitates nature, to a creator, one who brings forth new truth from the self’s expression

- The imagination of offers a realm of reality that science cannot offer. Aesthetic standards become "organic"

- Nature becomes the organic world, which is unified by the spirit of the World Soul.

- At first, society is regarded as simply corrupt, but later romanticism takes on a new belief in social action as the expression of truth in history.

Aspects of Euro-American Realism (ca. 1865-1914)

Widespread historical changes in the nineteenth century:

Widespread historical changes in the nineteenth century:

- an acceleration in the growth of the Industrial Revolution, rapid transportation, and population growth.

- a number of reactionary movements, some reconsidering medieval social cooperation, Christian or Marxist socialism, or "art for art’s sake"

- Darwinian evolution, French positivism, and social evolution

- growing doubts in eventual progress and superiority of Western civilization

- British utilitarianism

- Realistic portrait of contemporary life; to present life as it really occurs. Often, it focuses on either middle-class life or the perverse, the vulgar, and the criminal.

- Stress on a belief in scientific materialism, a rejection of romanticism

- Stress on political, social reforms

- Distrust of traditional novelistic patterns; life, after all, lacks symmetry and form.

- Stress on the inner lives of characters; seeks to give an honest portrait of human inwardness.

Aspects of Naturalism (ca. 1870-1930)

- A belief in scientific determinism, that humans are a product of evolutionary and social determinism.

- Life and history are fueled by competition

- The novel is, like a laboratory, studying life empirically.

- Tends to see life and nature as amoral, a product of chance forces.

- Humans are one more species of animal controlled by hunger, anger, fear, and sexual desire.

Aspects of Symbolism (ca. 1857-1930)

- An extension of the romantic notion of self-consciousness and metaphor.

- Stresses multiple perspectives and the resources of the senses.

- Language as the form of symbols points to another, the larger plane of existence that cannot be understood through scientific, rationalistic methods

- Language is highly controlled to produce its effects.

- More interested in the allusive and the fragmentary.

- It had a large influence on early twentieth-century modernism.

Aspects of (Western) Modernism (ca. 1914-1965)

- A partial break with romantic and realist movements, yet some modernist art continues to borrow from these.

- Solipsism: the world is experienced as we perceive it. Some go as far as to argue that we create the world through the act of perception.

- Stress on historical fragmentation, alienation, loss, despair, and angst. A desire to bring out of this some experience of order and/or form.

- History is a subjective portrait.

- Deeply influenced by Freudian portraits of the subconscious.

- Stress on complex, dense, polyvalent forms.

- Adopts methods such as surrealism, futurism, and stream-of-consciousness to express the above.

- An interest in existentialism: the creation of personal meaning, the absurdity (or mystery) of existence.

- Also influenced by shifts in the sciences:

- Einstein (theory of relativity)

- Heisenberg (uncertainty principle)

- Kuhn (paradigm shifts)

- Godel (multiple, exclusive logics)

- Its influence (for better or worse) is spread around the globe through colonialism.

Aspects of Post-Modernism (ca. 1965-present)

- An extension or a break with twentieth-century modernism. It continues to stress modernist traits of fragmentation, solipsism, alienation, and subjective history.

- Yet it also rejects modernist interests in symbols and form for an interest in the surface, chance, the impersonal, and/or local.

- Strong interest in post-structuralism and deconstruction, theories that find language’s ability to communicate highly problematic. All language is tied to what it seeks to describe. No objectivity.

- Often stresses a cool, detached, emotionally uninvolved style.

- Argues that no coherent, unified reality is possible.

- The (dis)connection between modernism and post-modernism can also be seen not as two discrete movements, but as two poles of an experience:

| Modernism | Post-Modernism |

| romanticism/symbolism | surrealism/dadaism |

| form/function | anti-form/disjunction |

| purpose | play |

| design | chance |

| hierarchy | anarchy |

| mastery/logos | exhaustion/silence |

| art object/finished | process/happening |

| creation | deconstruction |

| presence | absence |

| centering | dispersal |

| root/depth | surface/rhizome |

| interpretation | (mis)reading |

| grand narrative/universal | local history only |

| erotic | androgynous |

| origin and cause | indeterminacy |