Omeros: What is an Epic?

What is an Epic?

"A long narrative poem in elevated style presenting characters of high position in adventures forming an organic whole through their relation to a central figure and through their development of episodes important to the history of a nation or a race." (Harmon & Holman. A Handbook to Literature. 7th ed.)

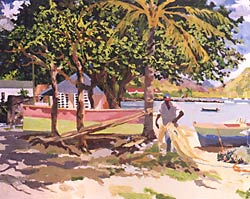

"Preparing the Net," 1999, oil on canvas by Derek Walcott.

Characteristics of an Epic

- Characters are larger-than-life beings of national importance and historical or legendary significance.

- The setting is grand in scope, covering nations, the world, or even the universe.

- The action consists of deeds of great valor and courage.

- Style is sustained in tone and language.

- Supernatural forces interest themselves in human action and often intervene directly.

Particular Epic Techniques in the Western Tradition

- An invocation to the Muse for inspiration in the telling of a story.

- Epics tend to start in media res. "In the middle of the action."

- Epic catalogs list warriors, armies, etc.

- Descent to the Underworld

- Dialogues tend to be extended, formal speeches.

- Epic similes are frequent epic simile: "a long, grand comparison which is so vivid that it temporarily displaces the object to which it is compared."

Questions about Omeros' Epic Nature

Look over the general definition and characteristics of an epic.

- Which aspects of these has Walcott adopted for his epic?

- Which aspects has he altered?

- What is he trying to suggest by doing this--about the nature of the Caribbean? about the nature of heroics? about the nature of race and culture?

"Omeros" 1990, oil on canvas by Derek Walcott

Look at the invocations (chapter 2, sec. 2; chapter 13, sec. 3; chapter 59, sec. 2; chapter 64, sec. 1).

- What does he praise about Omeros?

- Why does he pray and/or invoke "my Zero"?

- Why does he praise the Sun?

- What are the characteristics of Achille that Walcott praises? What is he choosing to stress about Caribbean life here? Compare this with the invocation to Homer's Iliad translated below.

"Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest."Homer. Iliad Book 1. trans. Samuel Butler.

Look at the epic catalogues in chapters 38, sec. 3 and 52, sec. 2. Why would Walcott put together such lists?

Read the extensive dialogue between Achille and his ancestor Afolabe in chapter 25, sec. 3. What do we learn about the nature of Achille's lost heritage?

Walcott at points makes various religious references. Why does he include the following?

- The gods of weather during the hurricane (chapter 9, sec. 3)

- The gods of trees (chapter 1, sec. 2)

- The Christian God (chapter 4, sec. 2; chapter 25, sec. 1

- The African gods (chapter 48, sec. 1)

- The sea swift has an almost religious power (chapter 4, sec. 2; chapter 24, sec. 1; chapter 47, sec. 3; chapter 63, sec. 3)

- Ma Kilman is regarded as a Sibyl figure (cf. chapters 47-49).

Look at the descents into the underworld. Why does he borrow the return to the dead in each case?:

- Achille's diving expedition is a kind of descent to the dead (chapter 8, sections 1-2).

- Achille's visit to Africa in a dream vision is a return to the ancestors (Book 3).

- Walcott accompanies Omeros to the Malebolge (Book 7).

Locate some examples of Walcott's similes

The most obvious epic battle is that of the Battle of the Saintes (Book 2).

The Larger Question of Omeros as an Epic

"I think any work in which the narrator is almost central is not really an epic. It's not like a heroic epic. I guess. . . since I am in the book, I certainly don't see myself as a hero of an epic, when an epic generally has a hero of action and decision and destiny."

--Interview with Rebekah Presson, 1992

"The whole book is an act of gratitude. It is a fantastic privilege to be in a place in which limbs, features, smells, the lineaments and presence of the people is so powerful. . . . And there is no history for the place. . . One reason I don't like talking about an epic is that I think it is wrong to ennoble people, . . . And just to write history is wrong. History makes similes of people, but these people are their own nouns."

--Derek Walcott

Walcott's Omeros is a work in conversation with the epic, but Walcott himself insisted that it is not a true epic. Along with those above, note some of the ways in which Walcott's long poem is in conversation:

The poem obviously builds off Homeric references--Hector, Achille(s), Helen, Philoctete, Paris, etc. Both Walcott and Plunkett see the epic connections in name and deed, but the text eventually calls it into question.

Walcott's relationship with his father's ghost has a Virgilian feel, as his relationship to Omeros has a Dantesque quality. Likewise, Catherine Weldon is a kind of conduit for Walcott:

- Warwick his father: chapters 12.1-13.3 & 36.3

- Catherine Weldon: chapters 34.3-35.3, 42.2-43.2

- Omeros: chapters 2.2-3, 28.1, 38.1, 39.3, 40.1-2, chapters 61-63.

Walcott's visit to Dublin and Joyce's ghost makes a subtle reference to Joyce's Ulysses. Likewise, his visit to the Malbolge is a nod to Dante's Inferno.

Note, however, how Walcott calls into question the epic project in reference to St. Lucia: chapter 45, sec. 2; chapter 62, sec. 2; chapter 64, sec. 2.