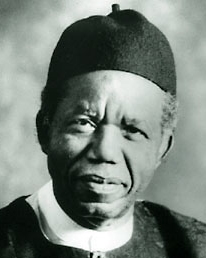

Chinua Achebe on The Purpose and Values of Things Fall Apart

Revising the Colonialist Damage

"Here, then, is an adequate revolution for me to espouse--to help my society regain its belief in itself and put away the complexes of the years of the denigration and self-abasement. And it is essentially a question of education, in the best sense of that word. Here, I think, my aims and the deepest aspirations of my society meet. For no thinking African can escape the pain of the wound in our soul [. . .] The writer cannot expect to be excused from the task of re-education and regeneration that must be done. In fact he should march right in front . . . I for one would not wish to be excused. I would be quite satisfied if my novels (especially the ones set in the past) did no more than teach my readers that their past--with all its imperfections ---was not one long night of savagery from which the first Europeans acting on God’s behalf delivered them. Perhaps what I write is applied art as distinct from pure. But who cares? Art is important but so is education of the kind I have in mind. And I don’t see that the two need be mutually exclusive."

-- "The Novelist as Teacher" (1965)

Achebe understands his role as a novelist to be educational but also reformational. He wants to set the records straight about the complexity and nobility of the Igbo people and their traditional way of life. He wants to correct his people's misconceptions about themselves, ones enforced by years of British imperialist education that has taught them that they are inferior.

The Colonialist Mind & Education

"To the colonialist mind it was always of the utmost importance to be able to say: ‘I know my native’, a claim which implied two things at once: (a) that the native was really quite simple and (b) that understanding him and controlling him went hand in hand—understanding being a precondition for control and control constituting adequate proof of understanding. Thus is the heyday of colonialism and serious incident of native unrest, carrying as it did disquieting intimations of slipping control, was an occasion not only for pacification by the soldiers but also (afterwards) for a royal commission of inquiry—a grand name for yet another perfunctory study of native psychology and institutions. Meanwhile a new situation was slowly developing as a handful of natives began to acquire European education and then to challenge Europe’s presence and position in their native land with the intellectual weapons of Europe itself. To deal with this phenomenal presumption the colonist devised two contradictory arguments. He created the ‘man of two worlds’ theory to prove that no matter how much the native was exposed to European influences he could never truly absorb them; like Prester John he would always discard the mask of civilization when the crucial hour came and reveal his true face. Now, did this mean that the educated native was no different at all from his brothers in the bush? Oh, no! He was different; he was worse. His abortive effort to education and culture though leaving him totally unredeemed and unregenerated had none the less done something to him – it had deprived him of his links with his own people whom he no longer even understood and who certainly wanted none of his dissatisfaction or pretensions. ‘I know my natives; they are delighted with the way things are. It’s only these half-educated ruffians who don’t even know their own people.’ How often one heard that and the many variations of it in colonial times!"-- "Colonialist Criticism" (1974)One of the problems with colonialist education is that the colonizers often assume they understand and know the people they have colonized, and this assumption of knowledge reinforces the oppressive institutions and claims of the oppressors. The colonizers often assume an inherent superiority on their part. Achebe describes the particular problem of being African and yet educated in the transplanted European institutions of education. Note how an estimation of someone also allows a certain continued kind of control.

Living at the Cultural Crossroads

"We lived at the crossroads of cultures. We still do now today; but when I was a boy one could see and sense the peculiar quality and atmosphere of it more clearly. I am not talking about all that rubbish we hear of the spiritual void and mental stresses that Africans are supposed to have, or the evil forces and irrational passions prowling through Africa’s heart of darkness. We know the racist mystique behind a lot of that stuff and should merely point out that those who prefer to see Africa in those lurid terms have not themselves demonstrated any clear superiority in sanity or more competence in coping with life. "But still the crossroads does have a certain dangerous potency; dangerous because a man might perish there wrestling with multiple-headed spirits, but also he might be lucky and return to his people with the boon of prophetic vision. "On one arm of the cross we sang hymns and read the Bible night and day. On the other arm my father’s brother and his family, blinded by heathenism, offered food to idols. That was how it was supposed to be anyhow. But I knew without knowing why it was too simple a way to describe what was going on. Those idols and that food had a stronger pull on me in spite of my being such a thorough little Christian that often at Sunday services at the height of the grandeur of Te Deum Laudamus I would have dreams of mantle of gold falling on me while the choir of angels drowned our mortal song and the voice of God Himself thundering: This is my beloved son in whom I am pleased. Yes, despite those delusions of divine destiny I was not past taking my little sister to our neighbor’s house when our parents were not looking and partaking of heathen festival meals. I never found their rice to have the flavour of idolatry. I was about ten then. If anyone likes to believe that I was torn by spiritual agonies or stretched on the rack of ambivalence he certainly may suit himself. I do not remember any undue distress. What I do remember was a fascination for the ritual and the life of the other arm of the crossroads. And I believe two things were in my favour—that curiosity and the little distance becomes not a separation but a bringing together like the necessary backward step which a judicious viewer may take in order to see a canvas steadily and fully.[. . .] Although I did not set about it consciously in that solemn way I know now that my first book, Things Fall Apart, was an act of atonement with my past, the ritual return and homage of a prodigal son." - "Named for Victoria, Queen of England" (1973)Stop and ask yourself why Achebe understands his novel as "an act of atonement" for his past. Are you comfortable with his vision of a cultural crossroads where both sides of his upbringing (Christian and pagan) are held together without any tension?