Flannery O'Connor and the Theology of the Grotesque

"Fiction doesn't lie, but it can't tell the whole truth. What would you make out about me just from reading 'Good Country People'? Plenty, but not the whole story. Anyway, you have to look at a novel or a story as a novel or story; as saying something about life colored by the writer, not about the writer colored by life. She distorts herself to make a better story so you can't judge her by the story."

-- Letter to "A," 19 May 56

grotesque: art that in both form and content, while appearing to be a part of the normal natural, social, or personal world, distorts, exaggerates, or combines the incompatible and strange with the seemingly typical in order to surprise and/or shock the audience. It invokes the bodily, the ugly, and often the "supernatural" in order to intrigue and yet repulse.

Theories of the Grotesque

(Wolfgang Kayser -- a negative position) 1) "The Grotesque is the estranged world"; 2) "an expression of an incomprehensible, inexplicable, and impersonal force"; 3) "a play with the absurd"; and 4) "an attempt to invoke and subdue the demonic aspects of the world."

(Geoffrey Galt Harpham -- a positive position) 1) The grotesque does not "fit our standard categories of identification"; 2) the grotesque has "a confused and incoherent energy and abidance"; 3) the grotesque "occupies a gap or interval" between what is and what could be; 4) the grotesque forces us to see a hidden truth we might otherwise ignore; 5) the grotesque mediates between the margins and the center; and 6) the grotesque represents a mythic encounter with "another kind of world."

(Wilson Yates -- a theologically centered position)

- The grotesque represents some aspect of the world that doesn't fit our normal preconceived notions; thus, it represents the margins or boundaries that we seek to ignore or forget.

- It is a distorted symbology of a reality that is itself deformed.

- The grotesque suggests that there are aspects of the world which we cannot easily comprehend; our experience of the grotesque should result in bafflement.

- The grotesque reminds us that the world is mysterious; we cannot ever acquire enough knowledge to render it completely explainable.

- It reminds us of our limited, if disturbing, creativity in the face of such a world.

- The grotesque unmasks the distortion and brokenness of the fallen world.

- The grotesque, ironically, may open us to the possibility of liberation, grace, even unity because it suggests that the first step towards these matters comes in confronting, even accepting, our distortedness, brokenness, and suppressed visions of the truth of the world.

O'Connor on Mystery, Evil, and Distortion

"It makes a great difference to the look of a novel whether its author believes that the world came late into being and continues to come by a creative act of God, or whether he believes that the world and ourselves are the product of a cosmic accident. It makes a great difference to his novel whether he believes that we are created in God's image, or whether he believes we create God in our own. It makes a great difference whether he believes that our wills are free, or bound like those of the other animals."

"I have to make the reader feel, in his bones if nowhere else, that something is going on here that counts. Distortion in this case is an instrument; exaggeration has a purpose, and the whole structure of the story or novel has been made what it is because of belief. This is not the kind of distortion that destroys; it is the kind that reveals, or should reveal."

"Either one is serious about salvation or one is not. And it is well to realize that the maximum amount of seriousness admits the maximum amount of comedy. Only if we are secure in our beliefs can we see the comical side of the universe. One reason a great deal of our contemporary fiction is humorless is because so many of these writers are relativists and have to be continually justifying the actions of their characters on a sliding scale of values."

-- "Novelist and Believer"

"In these grotesque works, we find that the writer has made alive some experience which we are not accustomed to observe every day, or which the ordinary man may never experience in his ordinary life. [. . .] If the novelist is in tune with this [modern] spirit, if he believes that actions are predetermined by psychic make-up or the economic situation or some other determinable factor [. . .] Such a writer may produce a great tragic naturalism, for by his responsibility to the things he sees, he may transcend the limitations of his narrow vision. On the other hand, if the writer believes that our life is and will remain essentially mysterious, if he looks upon us as beings existing in a created order to whose laws we freely respond, then what he sees on the surface will be of interest to him only as he can go through it into an experience of mystery itself. [. . .] He will be interested in possibility rather than probability. He will be interested in characters who are forced out to meet evil and grace and who act on a trust beyond themselves -- whether they know very clearly what it is they act upon or not."

-- "The Grotesque in Southern Fiction"

"The Catholic novelist believes that you destroy your freedom by sin; the modern reader believes, I think, that you gain it in that way. There is not much possibility of understanding between the two."

"To insure our sense of mystery, we need a sense of evil which sees the devil as a real spirit who must be made to name himself, and not simply to name himself as vague evil, but to name himself with his specific personality for every occasion. Literature, like virtue, does not thrive in an atmosphere where the devil is not recognized as existing both in himself and as a dramatic necessity for the writer."

-- "On Her Own Work"

Click here for Grotesque (Christian Worldview)

General Questions

- What are O'Connor's stories seeking to make us aware of? Are their worlds different from what we typically expect?

- What is mysterious, even baffling, about the stories?

- What is distorted & broken? What is not? How can you tell the difference?

- What do the stories symbolize?

- Is grace possible in any of the stories? Why or why not?

- Do you find any of the stories humorous? Why or why not?

"My current project is writing a talk I am to give to the Macon Parish Catholic Women's Council on the dizzying subject--'What Is a Wholesome Novel?' I intend to tell them that the reason they find nothing but obscenity in modern fiction is because that is all they know how to recognize"

-- Letter to John Lynch, 2 Sept 56

"A Good Man is Hard to Find"

"It's interesting to me that your students naturally work their way to the idea that the Grandmother in 'A Good Man' is not pure evil and may be a medium for Grace. [. . .] These old ladies exactly reflect the banalities of the society and the effect is of the comical rather than the seriously evil. [. . .] Grace to the Catholic way of thinking, can and does use as its medium the imperfect, purely human, and even hypocritical. Cutting yourself off from Grace is a very decided matter, requiring a real choice, act of will, and affecting the very ground of the soul. The Misfit is touched by the Grace that comes through the old lady when she recognizes him as her child, as she has been touched by the Grace that comes through him in his particular suffering. His shooting her is a recoil, a horror at her humanness, but after he has done it and cleaned his glasses, the Grace has worked in him and he pronounces his judgment: she would have been a good woman if he had been there every moment of her life."

--Letter to John Hawkes, 14 Apr 60

- What is O'Connor suggesting by presenting the grandmother and children as such narrow people?

- What is the grandmother's view of "blood"? Why does she recognize The Misfit as "one of my own children"?

- What is The Misfit's view of his past and of Jesus?

"The Life You Save May Be Your Own"

"Everybody who has read Wise Blood thinks I'm a hillibilly nihilist, whereas I would like to create the impression over the television that I'm a hillbilly Thomist. [. . .] When I come back I'll probably have to spend three months day and night in the chicken pen to counteract these evil influences."

--Letter to Robie Macauley, 18 May 55 on "the Life You Save" being made into a television drama.

- Characterize Mr. Shiftlet, the old woman, and Lucynell.

- How does the theme of deception play itself out in the story?

- What is the significance of the title?

- Why does O'Connor end with Mr. Shiftlet's interactions with the boy? Do Shiftlet's comments contain any truth in them?

"A Temple of the Holy Ghost"

"Purity strikes me as the most mysterious of the virtues and the more I think about it the less I know about it. 'A Temple of the Holy Ghost' all revolves around what is purity. [. . .] I never have anything balanced in my mind when I set out; if I did I'd resign this profession from boredom and operate a hatchery."

-- Letter to "A," 25 Nov 55

- Contrast Susan and Joanne's attitude towards life and their bodies with that of the child.

- What is the impact on the child knowing that she is "a Temple of the Holy Ghost"?

- How does the girl understand martyrdom and sainthood?

- What is the significance of the hermaphrodite's claim that "God made me thisaway"?

- Why does the story end with the child reflecting on both the hermaphrodite and the host?

"Good Country People"

"That my stories scream to you that I have never consented to be in love with anybody is merely to prove that they are screaming an historical inaccuracy. I have God help me consented to this frequently. Now that Hulga is repugnant to you only makes her more believable. [. . .] A maimed soul is a maimed soul."

Letter to "A," 24 Aug 56

- Characterize the following: Mrs. Hopewell, Mrs. Freeman, Joy-Hulga, Manley Pointer.

- How does Joy-Hulga's atheism/philosophy form her worldview? How does it contrast with Manley's?

- What is the significance of her losing the leg to Manley?

"Enduring Chill"

"The problem was to have the Holy Ghost descend by degrees throughout the story but unrecognized, but at the end recognized, coming down, with ice instead of fire. I see no reason to limit the Holy Ghost to fire. He's full of surprises."

-- Letter to Maryat Lee, 25 Aug 58

- Characterize Asbury. What is his view of his mother and sister? What is his view of himself?

- Why does he destroy everything he has written except his long letter to his mother?

- Compare Asbury's expectation (and dream) of the Jesuit with Father Finn.

- Characterize Asbury's relationship with Randall and Morgan.

- What is the meaning of the final scene? (c/c 377 with 381-82)

Everything That Rises Must Converge"

"What I hate most is its [a story by Eudora Welty] in the New Yorker and all the stupid Yankee liberals smacking their lips over typical life in the dear old dirty Southland. The topical is poison. I got away with it in 'Everything That Rises' but only because I say a plague on everybody's house as far as the race business goes.[. . .A reporter asked ] if I thought the race crisis was going to bring about a renascence (that wasn't the word she used but was what she meant) in Southern literature. I said I certainly did not, that I thought that was to romanticize the race business to a ridiculous degree."

--Letter to "A," 1 Sept 63

- Compare and contrast Julian with Asbury from "Enduring Chill."

- What distinguishes Julian's view of the world from his mother's? How does he respond to her racism?

- Does Julian understand African-Americans? Why or why not?

- How and why does Julian react the way he does to his mother's stroke?

- What is the significance of the last sentence?

"Revelation"

"I am not going to leave it out [the vision]. I am going to deepen it so that there'll be no mistaking Ruby is not just an evil Glad Annie."

--Letter to "A," 25 Dec 63

- Characterize Mrs. Turpin.

- Explain her view of class structures and why they don't easily work for her (491).

- Why does Mary Grace attack Turpin?

- What message does Turpin receive from God through Mary Grace?

- Describe the nature of her prayer to God in the hog pen (506-07).

- Why does she judge the old sow "as through the very heart of mystery"? (508)

- Describe her vision of heaven? What is its message?

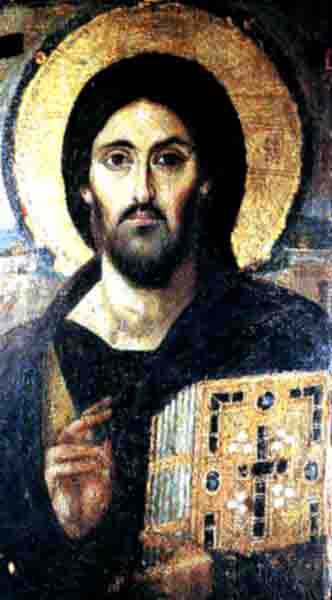

"Parker's Back"

"Sarah Ruth was the heretic--the notion that you can worship in pure spirit"

--Letter to "A," 25 July 64

- Compare and contrast Parker with Sarah Ruth.

- Why is he so attracted to her?

- What is the effect of the tattoo of Christ Pantocrator on Parker? (526 - 27)

- How does Sarah respond to the tattoo? (529)

- Why does the story end the way it does?

Final Question: Is O'Connor's worldview clearly present in her fiction? Why or why not?

General Observations

- The doctrine of sin and evil is most often present in O'Connor's fiction. The grotesque is there to awaken us to the state of fallenness in the world.

- Grace is most often present in a negative manner--at the point of awareness of our fallen state. The grotesque, often in a brutal manner, breaks in on our spiritual blindness. In some stories, grace has a more forgiving, comic place, e.g. "Revelation" and 'Enduring Chill."

- While O'Connor affirms the Christian doctrine of the victory of the sanctified life over sin, at times she almost indulges in a semi-Manichean dualism. Evil seems too strong in some stories.

- O'Connor should not be judged as a racist, but neither does she focus on political and social solutions to the South's deepest injustice. Instead, she tends to focus on the human dilemma of race relations and the personal problems of racism in the South.

- Her fiction does require a certain kind of reader, one who has awareness and openness to her message.

O'Connor, Flannery. Mystery and Manners. London: Faber and Faber, 1972.

-----. The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O'Connor. Sally Fitzgerald. Ed. NY: Vintage, 1980.

Yates, Wilson. "An Introduction to the Grotesque: Theoretical and Theological Considerations." The Grotesque in Art and Literature: Theological Reflections. James Luther Adams and Wilson Yates. Ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997.