Tolkien's "Northernness": Tolkien the Kolbítar

--R.M. Ballantyne, Erling the Bold: A Tale of the Norse Sea-Kings (1869)

"Yet I suppose I know better than most what is the truth about this 'Nordic' nonsense. . . .that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler. . . [r]uining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved, and tried to present in its true light. Nowhere, incidentally, was it nobler than in England, nor more early sanctified and Christianized. . . ."

--Letter to Michael Tolkien, 9 June 1941

"I have always with me: the sensibility to linguistic pattern which affects me emotionally like colour or music; and the passionate love of growing things; and the deep response to legends (for lack of a better word) that have what I would call the North-western temper and temperature. In any case if you want to write a tale of this sort you must consult your roots, and a man of the North-west of the Old World will set his heart and the action of his tale in an imaginary world of that air, and that situation: with the Shoreless Sea of his innumerable ancestors to the West, and the endless lands (out of which enemies mostly come) to the East. Though, in addition, his heart may remember, even if he has been cut off from all oral tradition, the rumour all along the coasts of the Men out of the Sea."

--Letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June 1955

History of Tolkien's Northernness

Tolkien's own "northernness" must be set amongst the larger culture trend in Victorian and Edwardian England of a reexamination and adoption of the Scandinavian and Germanic North--the Norse mythology of the Prose and Poetic Eddas, the Icelandic sagas, the exploration of Viking heritage, and so on. Northern mystique made it acceptable to claim direct and indirect lineage from Viking sources, to enshrine famous stories in family crests, artwork, and commercial products, and to see in the Icelandic culture a predecessor of representative government. The Saga of Frithiof the Brave, translated first by the Rev. William Strong, then followed by some 15 other English-language translations allowed Frithof to become a symbol of important period values--democracy, social improvement, and family.

In childhood, Tolkien first encountered Andrew Lang's retelling of "The Story of Sigurd," and it opened up for him a love of Norse myth. In secondary school, he began to learn Old Norse in order to read the original version, and he read a paper on the sagas before a literary club. While at Oxford, he included the study of Scandinavian Philology as a special subject, and he read translations to the Exeter College Essay Club. While teaching at the University of Leeds, his responsibilities included Icelandic studies, as they were when he began teaching at Oxford. There, he was part of the professorial reading group, the Kolbítars (Coal-Biters), who meet to read and translate the Eddas and sagas. In 1933, Tolkien was named an honorary member of the Icelandic Literary Society.

Norse Elements

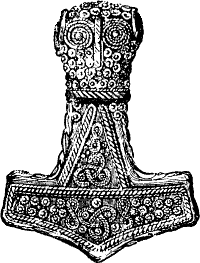

Source studies of Tolkien's work have identified a number of Norse elements he borrowed or reworked, one of the most famous being his names for the dwarves & Gandalf in The Hobbit, which are taken from the "Dvergatal" portion of Völuspá:

Nýi, Niði, Norðri, Suðri,

Austri, Vestri, Alþjófr, Dvalinn,

Nár, Náinn, Nípingr, Dáinn,

Bífur, Báfur, Bömbur, Nóri,

Órinn, Ónarr, Óinn, Miöðvitnir,

Vigr og Gandálfr, Vindálfr, Þorinn,

Fíli, Kíli, Fundinn, Váli,

Þrór, Þróinn, Þettr, Litr, Vitr ...

Hár, Hugstari, Hléþjófr, Glóinn,

Dóri, Óri, Dufur, Andvari...

Álfr, Ingi, Eikinskjaldi [Oakenshield]

Theory of Courage

Perhaps even more importantly, the Norse myths and sagas provided Tolkien with a mythological and literary flavor very different from that of the Greco-Roman myths. It opened up a world based on the "theory of courage," the willingness to continue even in the face of eventual cosmic defeat; it offered a world where the high and the low mix more freely, where the love of natural things is assumed, and where the natural and supernatural mix in a particular kind of wide, bracing love of the sea. In Tolkien's day the connection between Englishness and Northernness was considered deeply important, and in Tolkien's mind the Old Norse and Old English were simply two related families if not one family.

How Northernness is Incorporated

Just as Elias Lönnrot sought to construct a national epic for Finland and wove the Kaevala from Finnish myths and songs, so Tolkien set out to create a body of interrelated story and song that would create/discover the epic past of England. As the semester progresses, we will explore how this northernness works itself in the following ways in Tolkien's corpus:

- Tolkien's philological work, especially his love of sound

- His desire to offer a mythology for his country

- His nationalism, ethnicity

- His complex relationship to the theory of courage

- His political and economic views

- His ecological sympathies

- His Catholic Christianity

- The personalities and plots of some of his creations, including the feud at the heart of The Silmarillion, runes, riddle games, the dwarves, Bard, Rohan, and so on.