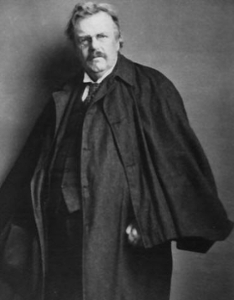

Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday (1908): Heresy, Anarchy, Madness, Egoism

"The word “heresy” not only means no longer being worse; it practically means being cleared-headed and courageous. The word “orthodoxy” not only no longer means being right; it practically means being wrong. All this can mean one thing only. It means that people care less for whether they are philosophically right. For obviously a man ought to confess himself crazy before he confesses himself heretical. The Bohemian, with a red tie, ought to pique himself on his orthodoxy. The dynamiter, laying a bomb, ought to feel that, whatever else he is, at least he is orthodox."--Heretics (1905)

"It is quite certain the realities like Zola do in one sense promote morality-they promote it in the sense in which the hangman promotes it, in the sense in which the devil promotes it. But they only affect that small minority which will accept any virtue of courage. Most healthy people dismiss these normal dangers as they dismiss the possibility of bombs or microbes. Modern realists are indeed Terrorists, like the dynamiters; and they fail just as much in their efforts to create a thrill. Both realists and dynamiters are well-meaning people engaged in the task, so obviously ultimately hopeless, of using science to promote morality. " --Heretics (1905)

"Imagination does not breed insanity. Exactly what does breed insanity is reason... if the madman could for an instant become careless, he would become sane. Every one who has the misfortune to talk with people in the heart or on the edge of mental disorder, knows their most sinister quality is a horrible clarity of detail; a connecting of one thing with another in a map more elaborate than the maze... Perhaps the nearest we can get to expressing it is to say this: that his mind moves in a perfect but narrow circle... The lunatic's theory explains a large number of things, but it does not explain them in a larger way." --Orthodoxy (1908)

"Anarchism adjures us to be bold creative artists and not care for laws or limits. But it is impossible to be an artists and not care for laws or limits. Art is limitation; the essence of every picture is the frame. . . . The moment you step into the world of facts, you step into a world of limits. You can free things from alien or accidental laws, but not from the laws of their own nature." --Orthodoxy (1908)

Anarchism

- A series of political and philosophical movements beginning in the late 18th century, though having their greatest influence between the 1840s and 1930s. Anarchism holds that all forms of social coercion should be dismantled or even destroyed--civil government, law enforcement, the legal system, etc. Typically, anarchists hold that free of these institutions, humans would form independent free associations in which people tend to act rightly.

- While some anarchists were pacifists, many held that organized terrorism was a necessity to overthrow corrupting leaders and institutions. A number of anarchists cells were responsible for the murders of public officials in Europe and Russia.

- Some, but not all, were philosophical nihilists and/or proponents of Nietzschean ideas, such as the superman, a transvaluation of ethics, and the will to power.

- Some anarchists were radical individualists, while others valued a collectivist approach. Most believed that order would arise in spontaneous fashion once free of compulsive government.

- Anarchists were also divided over whether individuals should control the means of production.

Distributism

Chesterton, like his good friend Hillaire Belloc, considered himself neither a capitalist nor a socialist, but embraced a position known as distributism, which was inspired by the teachings of Leo XIII in encyclicals such as Rerum Novarum and in the 1930's by Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno. While not all distributists were Catholics, the position was most often associated with Catholic thinkers and activists, such as Eric Gill, Vincent McNabb, and Dorothy Day. Its key teachings included:

- The distribution of property across the widest possible number of people. This was thought to be maximized by small farms, independent shopkeepers, craft guilds, and so on.

- The principle of subsidiarity, which holds that all power and action should be carried out at the lowest level of organization necessary. Big government should be strictly limited to matters of national concern. Not all distributists were anti-monarchical.

- Centralization is the least efficient way to take care of things--"Small is beautiful." Act locally.

- The Napoleonic division of property among all heirs is best.

- Workers should all have disposable shares in a business.

- House and homeland are more important values than race and empire. Family is at the center of production and social life.

- Economic and political arrangements should maximize human freedom and its responsibilities.

- All human beings are equal and made in the image of God. All the above follows from this truth.

- Distributists were divided over the role of machinery in work and common life. Chesterton was more open to the benefits of modern machinery.

- Likewise, not all distributists were agrarian in their ideals. Chesterton was more comfortable in town life.

Discussion Questions

- What does the opening poem to Clerihew Bentley reveal about the friends' past and present intellectual lives? What does it suggest about Chesterton's current view of Western culture?

- Why open the novel in Saffron (i.e. Bedford) Park, a fashionable neighborhood for intellectuals and artists?

- What makes Gregory and Syme alike? How do they differ?

- What do Syme's choices of vocation reveal about him? What do they reveal about fin-de-siécle Europe?

- What is the philosophical police? Should we take them seriously?

- Why does Syme want to strike down Sunday? Are his motives admirable?

- Can one parallel Syme's relation to Gregory with Wilks' to the real Professor de Worms?

Reflection Questions

- Can ideas be heretical? Should someone be killed for an idea?

- What makes something fanatical? What makes something mad or sane? Is Chesterton right to suggest a connection between logic and madness?

- Are humans free? If so, in what sense?

- Is government necessary? How much? In what capacities?

- Are social institutions responsible for human failings? Should they be dismantled or destroyed?

- What makes us afraid? What makes us angry? Does the first half of the novel offer any insight into these emotions?

- Is there anything admirable about the anarchists?